MSGC : Featured Windows : Current Window

Featured Windows, September 2006

St. Paul the Apostle Church (formerly St. Joseph's Catholic Church)

Building: St. Paul the Apostle Church (formerly St. Joseph Church)

City: Calumet

State: Michigan

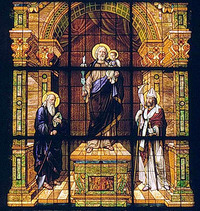

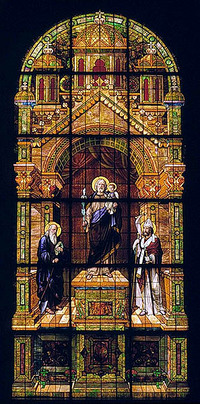

St. Joseph and the Christ child (center), flanked on either side by the saints Cyril (left) and Methodius (right), patrons of the unity of the Eastern and Western churches. Some faithful have reported seeing "the agonized face of Mary" in the left side of St. Joseph's cloak when viewing this window.

1

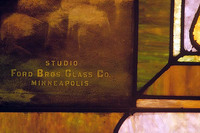

On the morning of May 8, 1906, the newly constructed St. Joseph's Church of Calumet, MI received its greatly anticipated new stained glass windows. The windows, created at the Ford Brothers Glass Company of Minneapolis, arrived along with a "force of experts" from Ford Brothers, with plans for a "rushed" installation. The next day's Copper Country Evening News cited the value of the windows at "at least $4,000," part of an over $100,000 building project that was hoped to be completed by the following summer.

2

The largest window was a 24' x 10' depiction of the church's patron St. Joseph accompanied by the Christ Child, along with Saints Cyril and Methodius while most of the other windows were smaller depictions of individual patron saints, the Virgin Mary, and some small ornamental windows. The church was intended to be the stateliest Catholic Church in the region, rivaling even that of the cathedral in nearby Marquette.

3 The new church was officially dedicated on June 28, 1908, a celebration with much fanfare, including a marching parade of more than a mile long.

4 Founded in 1889 by Slovenian immigrants, the parish now known as St. Paul the Apostle was commonly called "the Austrian church" by outsiders.

5 It was built after fire destroyed the original parish in 1902. Designed by the Milwaukee firm of Erhard Brielmaier and Sons, the new church was built of red sandstone from nearby quarries in Jacobsville, taking five years to finish between 1903 and 1908. At Calumet's peak as a mining community, it had a large and ethnically diverse Catholic population dispersed between six churches. But when the copper industry and its population in Calumet declined, the churches consolidated into two parishes in 1966—St. Paul the Apostle and Sacred Heart Parish.

6

Perhaps the "rush" to get these windows in place had something to do with its extreme locale and anticipation of an early winter. Not too far from the absolute northernmost point one can travel and still be in Michigan, Calumet sits near the line between Houghton and Keweenaw counties on the Keweenaw Peninsula, at the northwest tip of Michigan's Upper Peninsula—extending into Lake Superior and bordered on the south by the Keweenaw Bay. A latecomer to the mid-century copper rush that brought exploration, prospecting and ultimately mass migration to the region, Calumet emerged in the 1860s as a substantial source of copper. In the 1870s, the Calumet and Hecla mines produced more than half of the nation's copper supply.

7 At its peak, Calumet had a population of over 40,000 people, many of whom were employed in the area's 20-plus mines. "The world's biggest mining camp," as historian Dave Engel describes it, the town was ethnically diverse, drawing new immigrant workers and their families in large numbers: "On Ellis island, they knew the name Calumet".

8 Calumet, as well as the nearby villages of Red Jacket and Laurium—the area was often collectively referred to as "Calumet"

9—benefited with "relative prosperity" from the booming copper industry, developing as a significant business and cultural center. But as the industry declined over the decades, the community of Calumet too would shrink, dipping to 850 people by 2002, 35 years after the area's largest mining company of Calumet & Hecla ceased operation in 1968.

10

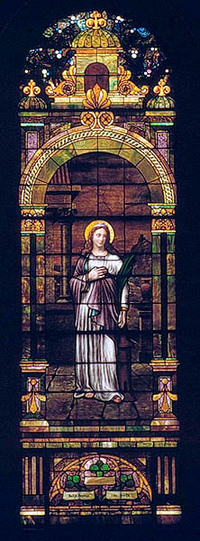

St. Roch (also Roc, Rocco, 14th century, French), pilgrim. Healed plague sufferers with the sign of the cross. When he was afflicted himself, he became a hermit, but was nursed back to health by a stray dog that fed him bread. One story tells of his false imprisonment and death in prison.

11 Patron of invalids, gravediggers, stonecutters, pavers and masons; invoked against infectious disease, sores and wounds of the legs.

12 In this window he is shown as he is often depicted, in pilgrim's garb, accompanied by a dog and pointing at his wounded/infected leg.

13

PATRON SAINTS FOR WORKERS IN PERIL

As we can well imagine without much effort, the life of the miners was difficult, dirty and constantly in peril. There was the constant fear of sudden injury or death due to fires or accidents in the mines.

14 It is only appropriate that the saints chosen for the windows representing Calumet's large population of Catholics with ties to the mines would be saints known to intercede on the behalf of workers in dangerous professions. For those who seek assistance from the saints in their daily lives, saints act as intercessors between the God and the living. This means that saints, although they have passed into heaven, still understand the worthiness of human needs as expressed through prayer, and are able to present these prayers to God. "[T]he saints who have reached the Father do not forget those they have loved on earth, their relatives and followers: they remember them before God and present to him their prayers and needs."

This idea of an extended famil[ial] relationship with the saint is where the concept of "patronage" or "patron saints" comes from. Additionally there is a legal connotation that suggests the saint as an advocate for the individual whom he/she represents. Patron saints are chosen for a variety of reasons, from their professions, to the manner in which their suffering and dying may be associated with particular objects or professions. Fernando and Gioia Lanzi's examples of St. Stephen (stoned to death) as a patron of stonecutters or St. Agatha (whose breasts were cut off) as a patron against breast tumors are excellent examples of this.16 Any given saint then might have numerous professions, places, animals, illnesses and so on that are under his or her purview for protection and intercession.

St. Joseph, for instance (the original patron of St. Joseph's/St. Paul the Apostle), was declared the protector of the Universal Church in 1870 by Pius I.17 As foster father to Jesus and protector of Mary he is the patron of fathers of families.18 Among other things, he is also the patron of carpenters, the dying, Canada, Belgium, and social justice.19 Joseph's status as a carpenter is significant, because he has come to be known as a patron of manual laborers.20 A recent pamphlet from St. Paul the Apostle aptly describes him as "honored above all other men as the personification of the dignity of labor, and as the provident guardian of workers' families."21 He is invoked often for "good death and against fear of death."22 He was a significant protector figure for the parishioners of this parish, as laborers, as fathers and their families, and as individuals seeking guidance and protection in a daily environment full of danger and uncertainty. The Joseph we see here is notably an elderly man. The Scriptures make no reference to Joseph's age, although in apocryphal writings he has been described as such. Lanzi notes that the general tendency has been to portray Joseph as a younger man. Joseph is portrayed here holding the Christ child, a common attribute; in fact it is less common to see Joseph portrayed outside of the role of fatherhood. His other attribute is that of his staff of almond flowers. Also from the apocrypha, the staff alludes to his selection as Mary's husband when a dove rests on his staff and to an episode in which the devil attempts to sway Joseph by telling him "if Mary's motherhood was divine, then his dry staff could flower—and the staff did flower."23

St. Barbara: "She is invoked by all who live in danger of sudden death."24

St. Barbara is another important figure for laborers in general and miners in particular because she is the patron saint of miners. Barbara is also patron to architects, builders, dying, fire prevention, founders, prisoners, and stonemasons.25 Barbara's origins, although generally set in the 4th century, are not a subject of agreement among scholars. According to David Farmer's Oxford Dictionary of Saints, Barbara's existence is doubtful, due to the fact that there is no evidence of a saint's cult for her. "Her Greek Acts, notoriously unhistorical, were not written until the 7th century; even more suspicious, Nicomedia, Heliopolis, Tuscany, and Rome all claimed to be the place of her death. This uncertainty did not prevent her cult [from] becoming very popular in the later Middle Ages, especially in France."26 Sandoval likewise describes her story as "religious fiction,"27 while Lanzi states that her cult "was established and widespread from very early times, but we have only vague information about her".28 Literary scholar Karen Winstead describes Barbara as one in a series of virgin martyrs in hagiography and material culture that is "remarkably homogenous" in their physical traits and in their manner of martyrdom.29 Such figures meet untimely, violent deaths—boiling, burning, dismemberment and so on—in the act of preserving their chastity.30 In their often serene representations in art, the only way to distinguish one of these martyrs, Winstead notes, is that she typically carries or wears the symbol of her suffering—such as a tooth, (St. Apollonia), her eyes (St. Lucy), a wheel (St. Katherine).31

Barbara's legend tells of the girl and her pagan father named Dioscorus, who locks Barbara in a tower to keep her out of the view of men. In her father's absence, Barbara is converted to Christianity. She moves into a bath-house her father is building, asking the workmen to add a third window in honor of the Holy Trinity. Discovering her conversion, Dioscorus turns the girl over to the authorities. Barbara is tortured and ultimately sentenced to death at the hand of her father. After slaying Barbara, Dioscorus is killed himself by a bolt of lightning.32

Barbara's association with thunder established a link to explosions, and therefore her invocation as a protector of miners, firemen, oil-workers artillerymen, and soldiers, among other dangerous professions.33 In the window here, we see Barbara with two of her principal attributes that often identify her, a tower and a peacock feather. The tower recalls her place of imprisonment and the windows she had built for the trinity—in some representations three windows may be visible. The feather recalls her suffering under torture in her legend, when the rods that were being used to beat her miraculously turned to peacock feathers.34

St. Paul the Apostle Church was registered in the Michigan Stained Glass Census by Joseph Medved of Calumet, MI. Photos by Eric Munch.

Notes:

- "The Windows of St. Paul's" (pamphlet). Michigan Stained Glass Census file 93.0040, Michigan State University Museum, East Lansing, Michigan.

- The stained glass windows, cost from to $900 apiece at the time. Ibid.

- "Windows Here." Copper County Evening News. 8 May, 1906.

- Engel, Dave and Gerry Mantel. Calumet: Copper County Metropolis. Rudolph, WI: River City Memoirs, 2002, p. 136.

- Thurner, Arthur W. Calumet Copper and People: History of Michigan Mining Community, 1864-1970. Hancock, MI: The Book Concern, 1974, p. 23.

- "St. Paul the Apostle Church" (pamphlet). Michigan Stained Glass Census file 93.0040, Michigan State University Museum, East Lansing, Michigan. In November of 1907, the Calumet News reported that 27,128 people in Houghton County were members of the Catholic Church, the largest concentration of whom being found in Calumet, which had a Catholic population of 13,141. At that time, there were six churches, to serve the needs of the various ethnic communities of Catholic faith within Calumet: St. Anthony's (primarily Polish), St. Anne's, St. Mary's, St. John de Baptiste (Croatian) Sacred Heart Church and St. Joseph's (Slovenian). St. Joseph's was the largest congregation, with just short of 3,000 congregants. Engel, p. 127.

- Thurner, p. 35.

- Engel, p. 5.

- Thurner, pp. 8-9.

- Engel, pp. 5-6.

- Lanzi, Fernando and Gioia. Saints and their Symbols: Recognizing Saints in Art and in Popular Images. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2004, pp. 169-70.

- Sandoval, Annette. The Directory of Saints: A Concise Guide to Patron Saints. New York: Dutton, 1996, p. 92.

- Lanzi, p. 170.

- Thurner, pp. 36-40. The Calumet News, which regularly tracked accidents and casualties in the local mines, reported a loss of 44 men in 1906 and 49 men in 1907, but also touted that the percentage of fatalities in Houghton county for 1907 (2.79% for a mining population of 17,579) was lower than that of other mining counties in the state (the next largest being Marquette, with 37 mining deaths a 5.49% casualty rate for a mining population of merely 6,744 workers). Engel, pp. 126-7.

- Lanzi, p. 13.

- Ibid., p. 14. There are actually several kinds of saints in the canon. While Old Testament usage of the term "saint" refers to the Israelites, the word came to mean the followers of Christ and ultimately those who suffered martyrdom as Christians. After Christianity became the official Roman religion in the fourth century, a death by suffering in the name of one's Christianity no longer was requisite for sainthood and the so-called "white martyrs" could earn their place among the sainted through lives of virtue and sacrifice. As the Roman Catholic Church grew in the following centuries, so did the number of saints canonized. Sandoval, pp. 2-3.

- Sandoval, p. 5.

- Lanzi, p. 42.

- Sandoval, p. 93.

- Farmer, David Hugh. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Second Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987, p. 239.

- "The Windows of St. Paul's" (pamphlet).

- Lanzi, p. 40.

- Ibid., pp. 40-42.

- Ibid., p. 96.

- Sandoval, p. 156.

- Farmer, p. 31.

- Sandoval, p. 156.

- Lanzi, p. 95.

- Winstead, Karen A. Virgin Martyrs: Legends of Sainthood in Late Medieval England. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997, p. 1.

- Ibid., pp. 1-18.

- Ibid., p. 3. Although this can certainly be said of other saints represented in art, Winstead's work addresses the "generic" quality of the virgin martyrs and their function in the construction of a paradigm of right womanhood.

- Farmer, p. 31; Sandoval, p. 156.

- Lanzi, p. 96. Interestingly, some of Barbara's other patrons include workers such as upholsterers and makers of brushes and felt hats, which Lanzi attributes to her name—"which suggests beards and therefore hair."

- Ibid., pp. 95-6.

Bibliography: Show Bibliography

Eckert, Kathryn Bishop. Buildings of Michigan. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Engel, Dave and Gerry Mantel. Calumet: Copper County Metropolis. Rudolph, WI: River City Memoirs, 2002.

Farmer, David Hugh. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Second Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Lanzi, Fernando and Gioia. Saints and their Symbols: Recognizing Saints in Art and in Popular Images. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2004.

Sandoval, Annette. The Directory of Saints: A Concise Guide to Patron Saints. New York: Dutton, 1996.

"St. Paul the Apostle Church" (pamphlet). Michigan Stained Glass Census file 93.0040, Michigan State University Museum, East Lansing, Michigan.

Thurner, Arthur W. Calumet Copper and People: History of Michigan Mining Community, 1864-1970. Hancock, MI: The Book Concern, 1974.

"Windows Here." Copper County Evening News. 8 May, 1906.

"The Windows of St. Paul's" (pamphlet). Michigan Stained Glass Census file 93.0040, Michigan State University Museum, East Lansing, Michigan.

Winstead, Karen A. Virgin Martyrs: Legends of Sainthood in Late Medieval England. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997. (MSGC 1993.0040)

Text by Michele Beltran, Michigan Stained Glass Census, September , 2006.