MSGC : Featured Windows : Current Window

Featured Windows, October 2010

The Divine Sarah

Building: Christ Church Cranbrook

City: Bloomfield Hills

State: Michigan

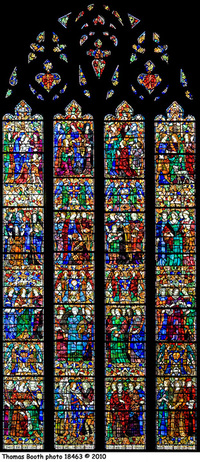

Top Left to Right: Panel#1; Motherhood (Hannah, Monica, Virgin Mary, Elizabeth). Panel#2; Christ’s Associates (Mary of James, Mary of Mark, Mary Magdalene, and Martha). Panel#3; Early Missionaries to Paul (Prisicilla, Lydia, Dorcas, and Phebe). Panel#4; Early Saints (Sts. Perpetua, Agnes, Felicitas,). Panel#5; Active in Religious Orders (St. Teresa, Catherine of Siena, St. Hilda, St. Clare). Panel#6; American Church Missionaries (Mary S. Francis, Julia C. Emery, and Ann C. Farthing). Panel#7; Educators, (Maria Mitchell, Alice Freeman Palmer, and Mary Mason Lyon). Panel#8; Nurses (Dr.Mary E. Glenton, Florence Nightingale, Clara Barton, and Edith Cavell). Panel#9; Musicians (Liza Lehmann, St. Cecilia, Cecile Chaminade). Panel#10; Artists (Vigee Lebrun, Mary Cassatt, and Maria Ann Kaufman). Panel#11; Poets (Amy Lowell, Emily Dickenson, Christina Georgina Rosetti, and Emily Jane Bronte). Panel#12; Novelists (Jane Austen, MaryAnn Evans, Charlotte Bronte, Louisa May Alcott). Panel#13; Sovereigns (Queen Elizabeth1, Queen Isabella, Queen Victoria). Panel #14; Liberators (Lucretia Coffin Mott, Joan of Arc, Harriet Beecher Stowe). Panel#15; Suffrage Workers (Dolly Madison, Susan B. Anthony, Anna Howard Shaw, and Elizabeth C. Stanton). Panel#16; Actresses (Sarah Siddons, Sarah Bernhardt, Mary Anderson, and Ellen Terry).

Florence Booth Beresford, the daughter of George and Ellen Scripps Booth, was the catalyst behind what is known as the

Women’s Window at Christ Church Cranbrook. The window is a unique concept designed by English artist James H. Hogan in 1927 and fabricated by James Powell &Son of London, England. It encompasses sixty renowned Biblical and historical women, divided into sixteen panel presentations in rows of four. The cognitive dissonance experienced during the 1920’s in regards to women’s suffrage and subsequent gender reform may have been expressed artistically in the

Women’s Window as a result of collective anxiety about changing social mores. The tension existing between two conflicting ideas of womanhood is seen first in the top eight panels which represent women known for their traditional female roles such as mothers, educators, nurses, and those active in religious orders. The representation of women in the lower eight panels seems to reconcile the conflict of modernity in late nineteenth century sensibility, by advocating women in their roles as musicians, artists, writers, sovereigns, suffrage workers, and actresses. An attempt at relieving this tension is witnessed in an inscription along the lower panel of the window from Proverbs 31:28, 31, verses chosen from a collection of moral teachings in the Bible which read: “Her children rise up and call her blessed…her works praise her in the gates.” Verses 10-31 in Proverbs contextually and culturally honor women for their physical and psychological strengths. However, it is a curious choice for the window, praising women in their conventional duties as spouses and homemakers, duties which are transcended in most of the window’s panels. Rather, it is the intangible virtues of womanhood that the viewer must search for in the stained glass images of the unconventional women portrayed.

All of the women represented are remarkable in their own right, claiming a portion of time and history upon which they readily left their mark. However, most are conspicuously in direct opposition to Proverbs’ detailed instructions of domesticity. Sarah Bernhardt is one such woman represented in the lower right Panel # 16. She was one of the greatest French actresses of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who challenged traditional social expectations of women. Bernhardt’s rags- to -riches story was fraught with scandal in her personal and professional life, including her numerous (often famous) lovers, her extravagant taste in clothing and furniture, and her countless idiosyncrasies. While her early career aspirations were supported through liaisons with men, Bernhardt’s relentless drive to become a great artist finally resulted in her financial independence. A skillful self-promoter and master of publicity, Bernhardt spent immense sums throughout her life constructing as well as enjoying an avant-garde image. In 1899 she took over a large Paris theater, renaming it Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt, and directed it until her death. Aware of the boundaries she was crossing, Bernhardt herself published an autobiography

Ma Double Vie in 1907. Embracing the pseudonym “The Divine Sarah," given her by French playwright Victor Hugo, Bernhardt becomes a perplexing personification of feminine virtue overlooking the nave at Christ Church Cranbrook. As an actress, Bernhardt was able to safely challenge the gender boundaries many of the other women noted in the window panels faced head-on. Ironically, the window’s inscription from Proverbs “applauds” this conflicting dynamic, praising women “in the gates.”

Born Henriette Rosine Bernard in Paris in 1844, of an unmarried Dutch Jewish mother, Bernhardt was marginalized in a bourgeois French society by her Jewish heritage and illegitimacy. Her mother, a courtesan, was an intermittent presence in her life and only with the help of a family friend was Sarah able to enter France's great drama school, the Paris Conservatoire. It was not until later that she rose to fame, in 1866 joining the Odéon Theater, where she had her first great successes. However, living the lifestyle of her mother, Bernhardt found herself tending to the demands of single motherhood, giving birth in 1864 to her only son Maurice, believed to be fathered by a Belgian aristocrat. The moral contradictions of single motherhood and the essence of marital fidelity demanded in Proverbs 31 is reconciled in Window Panel #1 in the exemplary prototypes of divinely initiated or “single” motherhood embodied in the Virgin Mary and Jesus, Elizabeth and John the Baptist, and Monica and her son St. Augustine, all of which correspond to the devoted relationship Sarah is known to have had with her beloved son Maurice.

Sarah Bernhardt was driven by humanitarian causes, specifically those that concerned the war effort. Her compassion and energy place her squarely in line with Lydia and Phebe, the early female missionaries represented in window Panel# 3, and the nurses Florence Nightingale, Clara Barton, and Edith Cavell in window Panel # 8, who directed nursing operations during times of war. Bernhardt’s “performance” in the war effort was commended, and she became a French “nightingale” in her own right, due to her work in supervising a clinic for wounded soldiers and establishing a military hospital in the closed Odéon Theater during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871).

Known as "the Golden Voice" for her extraordinary ability to deliver lines, Bernhardt mesmerized audiences with her unsettling beauty and graceful movements. She took on ingénue roles even as an elderly woman, and at sixty-five played the teenage French mystic Joan of Arc. The representation of such women as Joan of Arc is noted in Panel #14 aptly named the

Liberators, fulfilling a public need for saintly heroines. Joan of Arc is curiously positioned between American activists Lucretia Mott and Harriet Beecher Stowe, women whose abandonment of conventional female roles is in less tension with the Proverbs’ demand on women as wives and mothers, since the

Liberators mission was socially acceptable. Other Liberators titled as the

Suffrage Workers can be viewed in Panel #15.

In an interview for

Harper’s Bazaar, Bernhardt agreed that while playing male roles (such as Hamlet) was demanding, the complexity of the female character in Jean Racine's 17th-century tragedy

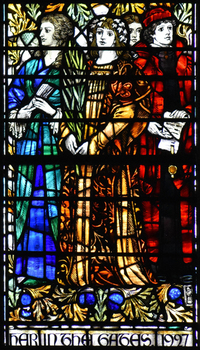

Phedre was her most difficult undertaking (fig.5). Perhaps because of this complexity, Hogan chose to represent Bernhardt in the

Women’s Window as the Grecian Queen Phedre, a misunderstood victim of her own moral shortcomings in a mythological tale fraught with incest, infidelity, and murder. Dressed in classical costume she is represented not in motherhood or as a fallen woman or saint, but somehow “safely” inbetween, embodying the ideals of Grecian splendor and nobility, standing passively erect in a reticent pose.

The representation of Bernhardt’s “body” as

Phedre is hidden beneath an Ionic type of classical costume known as a chiton, embroidered with an ornamental border typically worn by Greek women in antiquity. Bernhardt’s image may not only conceal her physical sensuousness and notoriety, but that of

Phedre’s as well.

Missing in the representation of Bernhardt as

Phedre is the classical pinned and encircled coif adopted by ancient Greek women. In an effort to further redeem Bernhardt’s Grecian alter ego, her image is sanctified by replicating the long, flowing hair of the “Virgin Saint,” better known as St. Agnes (Panel #4)

(left), and the fallen woman Mary Magdalene (Panel #2)

(right) who remind the viewer of the bondage of sin and the possibility of salvation. Regal and angelic in a subservient stance and attired in a golden chiton with a palm frond like Agnes’ in her hand (symbolic of resurrection), the “Divine Sarah” has risen above the judgment of mankind, empowering women, rather than exploiting them in tandem with Proverbs’ verses.

Sarah Bernhardt died on March 26, 1923 at age 79, only five years before her effigy was preserved for perpetuity in stained glass. Her ability to identify with the characters she played is legendary and was in part due to a mature empathy toward emotional suffering. Her epigram as the “Divine Sarah” gives her a starring role above the feminine spirit at Christ Church Cranbrook, as she embodied the female characters of saints and sinners figuratively as well as in real life.

Christ Church Cranbrook was registered in the Michigan Stained Glass Census by Shirley Dow Marthey of Bloomfield Hills, MI and Thomas Booth of Birmingham, MI.

Bibliography:

Show BibliographyAbrahams, Ethel Beatrice. 1908. Greek dress; a study of the costumes worn in ancient pre-Hellenic times to the Hellenistic age. London: J. Murray. 49-66.

Bernhardt, Sarah. "Men’s Roles as Played by Women," Harper's Bazaar (1867-1912); Dec 15, 1900; 33, 50; American Periodicals Series On line pg. 2113.

_____________. My Double Life: The Memoirs of Sarah Bernhardt.Bernhardt, Sarah, and Victoria Tietze Larson. 1999. SUNY series, women writers in translation. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Christ Church Cranbrook. “The Women’s Window” (2005). Bloomfield Hills, MI

Gold, Arthur, and Robert Fizdale. The Divine Sarah: A Life of Sarah Bernhardt. New York: Knopf, 1991.

Wisner, Arthur. Sarah Bernhardt: Her Artistic Life. New York: R.H. Russell, 1901.84-113.(MSGC 1994.0158)

Text by Linda Johnson, MSU American Studies doctoral candidate; photographs by Thomas Booth, Michigan Stained Glass Census, October , 2010.