MSGC : Featured Windows : Current Window

Featured Windows, July 2007

Wright’s Space: The Meyer May House and Beyond

Buildings:

Detroit Institute of Arts - Detroit, Michigan

Meyer May House - Grand Rapids, Michigan

Left: The Meyer May House (1908), Grand Rapids, MI.

Right: A view from the balcony showcases Wright's exotic exterior copperwork design, created under the supervision of Hermann Von Holst after Wright's departure to Europe in September of 1909

1.

People with even a casual interest in art glass and architecture are familiar with the name of Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959), one of the most well-known and influential architects of the twentieth century. The names of the places associated with him—Fallingwater, Coonley Playhouse, Dana-Thomas House, Unity Temple and Robie House, to name but a few—hold an almost sacred quality to those who follow his work. Reproductions of Wright's leaded glass designs appear on note cards, sun catchers and other items that are ubiquitous in bookstores and gift shops. So it must occur to those with an interest in Michigan's architectural stained glass: What about Frank Lloyd Wright? Is he anywhere to be found in Michigan?

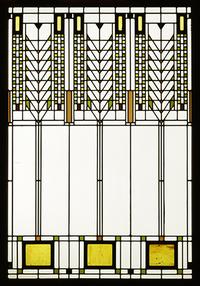

The quick answer is yes. There are many buildings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in Michigan. However, there are few examples of his leaded glass to be found here. We should step back for a moment and define our terms, however. Typically, we document stained glass windows—windows primarily made of colored glass—at the Michigan Stained Glass Census, and Frank Lloyd Wright's windows do not technically fall into that category. As stained glass consultant and scholar Julie Sloan notes in her work on Wright, the term "leaded glass" is more accurate, as a descriptive term for their method of assembly and because Wright's windows use clear glass predominantly over colored glass. Sloan also points out, however, that Wright did not call his own windows leaded, but preferred to use the term "light screens."

2

The one Frank Lloyd Wright house in Michigan we know of with leaded glass windows is indeed a lovely example—the Meyer May House of Grand Rapids (1908). Located at 450 Madison Avenue S.E., the house is a notable piece of Michigan architecture, even if it fails to get the attention given to other Frank Lloyd Wright Prairie-style houses. Even today, its presence on a street full of large, colorful Victorian homes is striking. In 1908 the effect must have been startling. Art historian Vincent Scully, who appears in the documentary of the May House restoration, The Renewing of a Vision, calls the Meyer May House, "a strange, moving kind of ruin, stretching out against the landscape, with these deep overhangs…with the enormously high, erratic, really Mayan, very Amerindian detail. It's like a temple. And it really doesn't go with the others."

3

Left: The May House guest entry, featuring a Hollyhock mural by George Niedecken on the left, recovered from under six layers of paint during restoration

4.

Right: A stair landing wall of glass, the tallest windows measuring almost 10 feet high.

Construction on the two-level brick house for Grand Rapids clothier Meyer May and his wife Sophie began in 1908 and was completed in 1909, while Wright was abroad

5. As Wright aficionados know, Wright had in fact absconded to Europe at that time with Mamah Borthwick Cheney, the wife of a Chicago client

6. In this period of his absence, his studio was left in the hands of Chicago architect Hermann Von Holst

7. Between 1910 and 1917 George Niedecken, a Milwaukee-based associate of Wright, completed interior work on the house

8. After Sophie's death in 1917, May remarried in 1921 to Rae Stern, a Chicago widow with two children. He added additional bedrooms and servants' quarters in 1922, designed by the firm of Osgood & Osgood. The May-Stern marriage ended in divorce after eight years, and May himself died in 1936.

After May's death, the house remained unoccupied until its sale in 1942. At this point, it was rezoned for multi-dwelling use. The house changed hands several times and underwent numerous modifications over the next four decades. In 1985 the house was purchased by Steelcase, the Grand Rapids-based office furniture company. After a period of extensive historical research and restoration, the home was made open to the public in 1987

9. Restoration of the May House is a tale in itself documented admirably in the film The Renewing of a Vision. With the assistance of family photographs provided by May's children and the Prairie Archives of the Milwaukee Art Museum, a painstaking process of restoration when possible and replication when needed took place, of every element from carpet designs and paint colors to the choice of flowers for the home's exterior. Of the home's 116 copper plated, zinc-camed windows, few had damaged glass. The task of restoring the windows went to local glass artisan Mike Mackenzie of Grand Rapids Art Glass

10.

Left: Clerestories and electric skylights extend the open effect of a wall of casement windows in the May living room.

Right: Note the low eye level at which Wright set his windows and horizontal moldings—custom fit to his short-statured client Meyer May

11.

Wright's innovative four-poster dining room table. The leaded glass Wright designed for the May House is characteristic of his work in other Prairie-style homes, although scholars have pointed out that his May House designs were less elaborate than in other homes. Sloan notes that this allowed him to "dominate the interior"

12 with it, which he certainly did. There are leaded windows in every room of the house, from the kitchen and maid's quarters to the entry ways and bedrooms. The largest rooms have bands of casement windows utilizing a subtle chevron motif

13, sometimes with leaded doors leading to the exterior, while humbler rooms like bathrooms might have small single or pairs of windows. Wright experimented with electric lighting in several places in the May House, including his four-poster dining room table with electric lights and his use of electrically-lit skylights, most prominently used in the living room

14.

Left: The living room fireplace with Wright-designed andirons.

Right: Detail of the smaller scale master bedroom fireplace, utilizing bits of golden glass in the mortar.

Another innovative use of glass involved Wright's design of the fireplaces—one in the master bedroom and one in the living room. Wright had masons embed bands of autumnal-hued iridescent glass in the mortar joints. When the glass catches the light a certain way, it "appears to dissolve in the light and only the bricks remain."

15

It is unclear at this point in time who actually created the leaded windows for the Meyer May House. Frank Lloyd Wright designed them of course, but he was not a stained glass artist. Wright had several studios he favored for the production of leaded windows in his Prairie homes, primarily in Chicago, including the Linden Glass Company, Giannini & Hilgart, and Temple Art Glass. He also worked with the Judson Studios of California. Sloan notes that it was the Linden Glass Company that appears to have executed the majority of the Wright's commissions during this period,

16 although specific documentation regarding the design and production of windows in Wright's buildings generally is lacking.

As for Wright's presence elsewhere in Michigan, there are over 30 buildings that have been attributed to Wright, although not all without argument. Art Historian A. Dale Northrup states that Wright designed over 1,000 structures for Michigan, of which 72 were houses, and of which 32 were actually built

17. In The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, which catalogs Wright's works around the country, William Allin Storrer comes to the same number, with some variation from Northrup's list. A key difference of particular interest to us—because the building is known to have leaded windows—would be the matter of the David M. Amberg House (1909), in Grand Rapids. While Wright claimed the building (built for Meyer May's father-in-law, and not far from the May House in locale) and to this day the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation lists it among his work, scholars and enthusiasts disagree, and for good reason. The official word from the Wright Foundation, upon inquiry, is that the Archives considers the Amberg House to be a H.V. Von Holst design. A design for the Amberg House was published in the Western Architect of October 1913 under Von Holst's name, with Marion M. Griffin listed as Associate

18.

David M. Amberg House, 573 College Avenue, Grand Rapids, Kent County, MI (H.V. Von Holst, designer). South (front) elevation. Historic American Buildings Survey, Allen Stross, Photographer. May 1965. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS, MICH,41-GRARA,7-2.

Although there are many other Frank Lloyd Wright-designed homes in Michigan, Wright chose for the most part to utilize methods other than leaded glass to bring light into his spaces. As Wright scholar Carla Lind notes, Wright enjoyed using glass to manipulate light in many ways. While many of his Prairie School period buildings utilized leaded glass windows, skylights and other fixtures, he continued to experiment with techniques such as using invisible corner joints and clerestory windows constructed of perforated plywood panels with fret-sawn geometric patterns

19. A fine example of Wright's use of glass in his later, Usonian style in a Michigan home would be the Melvin Maxwell Smith House of Bloomfield Hills (not pictured), built in 1946

20.

The only other known locations in Michigan of several leaded windows designed by Frank Lloyd Wright would be not houses, but museum collections. Interestingly enough, the source of most of those windows is not a Michigan home at all but a well-known site in Buffalo, NY—the Darwin D. Martin House (1904). Both the Detroit Institute of Arts and the University of Michigan Museum of Art (Ann Arbor) have windows from the Martin House

21. Martin, who along with his brother William was a longtime client and financial supporter of Wright,

22 earned his fortune with the Larkin Soap Company of Buffalo. Wright also designed the Larkin Company Administration Building in Buffalo (1903, demolished 1949-50) as well as the Martin brothers' E-Z Polish Factory in Chicago (1905)

23. Art Historian Robert McCarter notes that part of the Martin House Complex's importance comes from the fact that Wright took such care in forming an integrative design between the interior and exterior structures, as well as with its landscape architecture

24. The six-building complex, built between 1903 and 1905, included Martin's house and the George Barton House, as well as a pergola, conservatory, garage-stable and gardener's cottage. Unlike other Wright projects, this work was extensively documented in correspondence between Wright and Martin during the period of its design and construction, now at the Archives of the University of Buffalo. The Martin House contains over 200 individual art glass doors, windows and skylights. While Martin attempted to bring in a local fabricator, Wright ultimately got his way and contracted with the Linden Glass Company to work on the project for the quite high price at the time of $475. Martin House Curator Jack Quinan notes that Linden was unable to meet all of Wright's demands on the massive project, and that some of the work had to be turned over to Giannini & Hilgart and the Temple Art Glass Company

25. Although the dominant window design motif in the Darwin Martin House is commonly described as the "Tree of Life"—like this window from the Detroit Institute of Arts' collections — the origin of the name is unknown. Sloan describes the pattern as a series of descending chevrons, a more elaborate version of the motif that appears in the Meyer May House windows

26.

Left: Darwin D. Martin House, 125 Jewett Parkway, Buffalo, Erie County, NY. Detail of south (front) elevation from southwest. Historic American Buildings Survey, Jack E. Boucher, Photographer. May 1965, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS, NY,15-BUF,5-4.

Right: Window, 1904, Frank Lloyd Wright, Founders Society Purchase, Dr. and Mrs. George Kamperman Fund and Friends of Modern Art Fund. Photograph © 1986 The Detroit Institute of Arts.

Two years after Darwin Martin's death in 1935, his wife moved out of the house and his son stripped it of many of its windows and other fixtures. For years, the empty house suffered thefts and vandalism, and the city of Buffalo seized it as payment for back taxes in 1946. From 1954 to 1965 an architect named Sebastian Tauriello cared for the home, but modified it into apartments and demolished the damaged pergola and garage. It was not until the 1990s, when the home had come under the stewardship of the State University of New York at Buffalo that a massive restoration campaign took place

27. As of 2002 the Martin House Complex was transferred to a non-profit organization, the Martin House Restoration Corporation. Because of the original loss of so many fixtures from the Martin House, pieces have been scattered into museums and private collections all over the world. Some pieces are still unaccounted for. The irony of the Martin House's infamous dispersion outside of Buffalo is that it has become an entity both known and unknown. While the dispersal of its windows and other fixtures is unfortunate, it has created an access to Wright's work through public collections that he could never have possibly conceived. Although it could be argued that the context Wright intended is completely lost in viewing his windows in a museum setting, the alternative could be what we know happens when less well-known buildings meet similar fates— pieces vanish into private collections, they fall into architectural salvage, they simply get discarded. It is the combined efforts of art museums and historic house sites like the Meyer May House that give continued value to Wright's work and allow us to experience it.

All Meyer May photos by Pearl Yee Wong.

Notes:

1Sloan, Julie L.

Light Screens: The Complete Leaded-Glass Windows of Frank Lloyd Wright. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 2001, p. 268.

2Sloan, Julie L.

Light Screens: The Leaded Glass of Frank Lloyd Wright. New York: Exhibitions International in association with Rizzoli International Publications, 2001, p. 25.

3The Renewing of a Vision Frank Lloyd Wright, Meyer May House, Grand Rapids, Michigan. Grand Rapids, MI: Steelcase, 1987.

4Steelcase, inc, et al.

The Meyer May House: Grand Rapids, Michigan. Grand Rapids, MI: Steelcase, Inc, 1987, p. 11.

5ibid., p. 4.

6Ehrlich, Doreen.

Frank Lloyd Wright Glass. [Philadelphia?]: Courage Books, 2000, p.102.

7Alofsin, Anthony.

Frank Lloyd Wright—The Lost Years, 1910-1922: A Study of Influence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993, p. 27.

8George Mann Niedecken (1878-1945) of the Niedecken-Walbridge firm of Milwaukee provided interior elements such as furniture, carpets and lighting for several Wright houses between 1907 and 1918. Niedecken himself was a glass designer, but there is no record of his having ever designed any of Wright's windows. Sloan,

Light Screens: The Complete Leaded-Glass Windows of Frank Lloyd Wright, p. 342.

9Steelcase, inc, et al, p. 4.

10The Renewing of a Vision Frank Lloyd Wright, Meyer May House, Grand Rapids, Michigan. There are in fact 118 windows in total in the May House, and all but two are leaded. There is a large clear bay window in the living room and, oddly, a narrow 1 1/2" x 48 1/5" sliver of a window in the maid's bedroom.

11Steelcase, inc, et al, p. 7.

12Sloan,

Light Screens: The Complete Leaded-Glass Windows of Frank Lloyd Wright, p. 268.

13Julie Sloan has developed a typology of Wright's window designs that follows the evolution of his work from Pre-Prairie to Post-Prairie and identifies ten types of design motifs that appear in his work. The chevron, which appears in the May and Darwin Martin house windows, is noted as appearing in thirteen buildings of the "Prairie Period" with the May House being the last to use it as a major motif.

Light Screens: The Complete Leaded-Glass Windows of Frank Lloyd Wright, pp. 106-107.

14There is also a skylight in one of the upstairs baths.

15Ehrlich, Doreen.

Frank Lloyd Wright Interior Style & Design. Philadelphia: Courage Books, 2003, p. 152.

16Sloan,

Light Screens: The Complete Leaded-Glass Windows of Frank Lloyd Wright, pp. 339-40. Complicating the general matter of provenance somewhat is the fact that Wright did not necessarily directly design the hundreds of windows that were designed for many of his homes. Sloan notes that because work on the May House was well underway before Wright left for Europe, it is unlikely that Von Holst or longtime associate Marion Mahony were involved in the design of its windows, tending to attribute the designs to Wright. She also notes that although there is anecdotal record of other architects in Wright's firm having designed windows for various projects (including Mahony), Wright ultimately took credit for every design. Ibid., p. 268; 341-2.

17Northup, A. Dale.

Frank Lloyd Wright in Michigan. Algonac, MI: Reference Publications, 1991, p. 7.

18Berndtson, Indira. Administrator: Historic Studies, The FLLW Archives. Correspondence with author, 07 Jun 2007. Marion Griffin (Mahony) worked as a draftswoman for Wright for fourteen years. Wayne Andrews notes that she designed the living and dining spaces of the Amberg House. Andrews, Wayne.

Architecture in Michigan. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1982, pp. 138-9. Sloan suggests that the window designs of the Amberg House in particular may have been Mahony's work. Sloan,

Light Screens: The Complete Leaded-Glass Windows of Frank Lloyd Wright, pp. 341-2.

19Lind, Carla.

Frank Lloyd Wright's Glass Designs. San Francisco: Pomegranate Artbooks, 1995, pp. 27-33; 46-50.

20Northrup, pp. 69-70.

21The University of Michigan Museum of Art has two windows from the Martin House (Michigan Stained Glass Census file 06.0018, Michigan State University Museum, East Lansing, MI). The Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) has one window and two sidelights. In addition, the DIA has a piece from a lay light originating from the Meyer May House and a May House chair. Tottis, Jim. Curator, Detroit Institute of Arts. Correspondence with author, 19 Jun 2007 (Michigan Stained Glass Census file 94.0039, Michigan State University Museum, East Lansing, MI).

22Huxtable, Ada Louise.

Frank Lloyd Wright. New York: Lipper/Viking, 2004., p. 97.

23Storrer, William Allin.

The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright: A Complete Catalog. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1978, pp. 93; 114.

24Robert McCarter. "The Fabric of Experience: Frank Lloyd Wright's Darwin Martin House." In Quinan, Jack, ed.

Frank Lloyd Wright : Windows of the Darwin D. Martin House. Buffalo, NY: Burchfield-Penney Art Center: Buffalo State College Foundation, 1999, pp. 21-22.

25Jack Quinan, "Documentation of the Martin House Art Glass." in Quinan, 1999, pp. 31-33.

26Sloan,

Light Screens: The Complete Leaded-Glass Windows of Frank Lloyd Wright, p. 257.

27Huxtable, pp. 97-99.

Bibliography:

Show BibliographyThe Renewing of a Vision Frank Lloyd Wright, Meyer May House, Grand Rapids, Michigan. Grand Rapids, MI: Steelcase, 1987.

Alofsin, Anthony. Frank Lloyd Wright-The Lost Years, 1910-1922: A Study of Influence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Andrews, Wayne. Architecture in Michigan. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1982.

Berndtson, Indira. Administrator: Historic Studies, The FLLW Archives. Correspondence with author, 07 Jun 2007.

Ehrlich, Doreen. Frank Lloyd Wright Glass. [Philadelphia?]: Courage Books, 2000.

Ehrlich, Doreen. Frank Lloyd Wright Interior Style & Design. Philadelphia: Courage Books, 2003.

Huxtable, Ada Louise. Frank Lloyd Wright. New York: Lipper/Viking, 2004.

Lind, Carla. Frank Lloyd Wright's Glass Designs. San Francisco: Pomegranate Artbooks, 1995.

Northup, A. Dale. Frank Lloyd Wright in Michigan. Algonac, MI: Reference Publications, 1991.

Quinan, Jack, ed. Frank Lloyd Wright : Windows of the Darwin D. Martin House. Buffalo, NY: Burchfield-Penney Art Center: Buffalo State College Foundation, 1999.

Sloan, Julie L. Light Screens: The Complete Leaded-Glass Windows of Frank Lloyd Wright. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 2001.

Sloan, Julie L. Light Screens: The Leaded Glass of Frank Lloyd Wright. New York: Exhibitions International in association with Rizzoli International Publications, 2001.

Steelcase, inc, et al. The Meyer May House: Grand Rapids, Michigan. Grand Rapids, MI: Steelcase, Inc, 1987.

Storrer, William Allin. The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright: A Complete Catalog. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1978.

Tottis, Jim. Curator, Detroit Institute of Arts. Correspondence with author, 19 Jun 2007. (MSGC 1995.0051, 1994.0039)

Text by Michele Beltran, Michigan Stained Glass Census, July , 2007.