Featured Windows, August-September 2010

Pens of Prophecy

Building: First Presbyterian Church

City: Royal Oak

State: Michigan

First Presbyterian Church, Royal Oak, MI. Sanctuary Space. The Prophets Window is on left wall closest to altar.

The Prophets Window is one of five windows on the west elevation that portray a wide-ranging compilation of many classical motifs and scriptural beliefs depicting the evolution of Christianity from its origins in the Mosaic temple rituals that were interpreted as typologically foreshadowing the life, death, and resurrection of Christ. The prophets represented are Isaiah, Jeremiah, Daniel, Hosea and Malachi. Each window is divided into six sections by steel head T-bars that are set in stone approximately 3 feet from the floor. This distance engages the viewer to read the window’s paneled sections beginning at the bottom, which naturally follows the chronology of prophetic literature, setting in motion biblical history from the Old to the New Covenant.

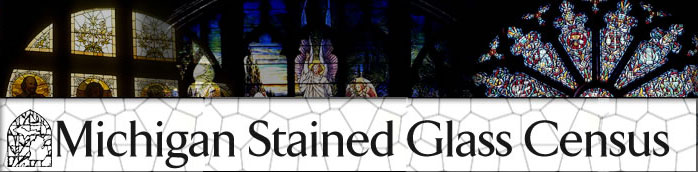

Isaiah. First Presbyterian Church, Royal Oak, MI 1952, designed by Marguerite Gaudin (1909-1991) and fabricated by the Willet Stained Glass Studios of Philadelphia, PA (1954-1980).

Isaiah (740B.C.) is clearly represented as partaking in the Hebrew ritual and practice of atonement for sin (Isaiah 6:13). He is kneeling in a repentant position above a temple arch, dressed in a purple robe symbolic of humility and without protective foot covering suggestive of being on Holy ground. He awaits redemption afforded through the temple ritual of purification and prayer. Because there is no atonement without sacrifice, the four-winged seraphim touching hot coals to Isaiah’s lips is necessary, as the coals are known to be charred by the blood of an innocent animal at the temple altar. According to Christian thought, this practice of sacrificing innocent animals typologically foreshadowed the death of Christ. (Hebrews10:5-13). Through this metaphorical “death,” Isaiah is cleansed from his sins. This image depicts the possibility of the removal of guilt and the commissioning of hope and salvation in a time of sin and disobedience in the last years of the southern kingdom of Judah. In vivid words and actions the prophet called the people and their leaders to a life of righteousness, warning that without repentance God would bring destruction.

Despite Isaiah’s feeling of impending doom, he states in 6:5 that he “has seen the King, the Lord Almighty.”This prophecy is portrayed in the oval inset of an early representation of Christ sitting on the mercy seat of the ark of the New Covenant wearing a cruciform halo and giving a Byzantine blessing. Gold glass symbolizes the “dazzling light of God’s glory” in the Holy of Holies. The Christian dispensation is fulfilled in Isaiah’s prophecy as Christ upholds the Bible halfway open, becoming the transitional figure in God’s redemptive plan.

Jeremiah. First Presbyterian Church, Royal Oak, MI 1952, designed by Marguerite Gaudin (1909-1991) and fabricated by the Willet Stained Glass Studios of Philadelphia, PA (1954-1980).

Jeremiah, (650 B.C.), warns God’s people of the catastrophe of the Babylonian take over by King Nebuchadnezzar, the destruction of the Jerusalem temple and the subsequent exile of the Jewish nation. Jeremiah’s image represents the broken covenant with God, as depicted in the shattered fragments of the stone tablets. Believed to have been destroyed in 587-586 B.C. with the destruction of Solomon’s temple (Jeremiah 52). “God’s Word” is now being written on the heart of Jeremiah, visually embodied in stained glass. A scriptural verse from Jeremiah 17:1-3 portrays God “writing” again, with a “pen of iron” (6:1), this time on the hearts of his chosen people. Incised on the stained glass heart is the Latin maxim Nisi Dominus Frustra, translated “Without the Lord, everything fails.” This window conveys a telling jeremiad of God no longer dwelling with his people in the Holy of Holies in the Temple structure or on the tablets. Typologically, the image points to Jeremiah’s prophecy when there would be a New Covenant, one that God’s people would have written on their hearts, not on temples (Hebrews 8:10). Jeremiah picks up the pieces of a broken heart as well as the broken law, as his life and many of his people are spared, despite their many years of penance in Babylonian captivity.

In the small inset at upper right, Elijah (850B.C.) is depicted in a surrender position of humility, with bare feet and the palms of his “crucified-like” hands empty and turned open. Portrayed with a similar rays (light) piercing his heart from above, he too is the bearer of divine knowledge, in a time of disloyalty and division among the northern and southern kingdoms.

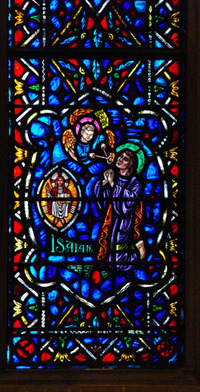

Daniel. First Presbyterian Church, Royal Oak, MI 1952, designed by Marguerite Gaudin (1909-1991) and fabricated by the Willet Stained Glass Studios of Philadelphia, PA (1954-1980).

The depiction of The Fiery Furnace in Daniel 3:8-30, shows the prophet (550B.C.), sitting with his right foot resting on a temple arch. Located in God’s “dwelling place” with the cloud of protection (Exodus 40:34) over his head, Daniel pauses from writing in an open book to look at his friends Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, who have survived the flames of the fiery furnace due to their unyielding faith in God. At the time of Daniel’s writing, Jews were in exile under the persecution of King Nebuchadnezzar, who perhaps is the astonished crowned figure above the prophet’s right side. Protecting his body with interlocked arms from the scorching heat of the kiln, the king looks out in disbelief over the “fire” of Daniel’s prophecies. The stories of Daniel and his fellow exiles are a more hopeful prediction of future religious toleration and triumph over their Babylonian and Persian enemies. Typologically as well as visually, Daniel has one foot grounded in the Mosaic Law of Hebrew Scriptures while his upward glance alludes to his imminent visions that foreshadow the Last Judgment in the Book of Revelation. 19:3, where it is the “Babylonians” who are consumed by fire.

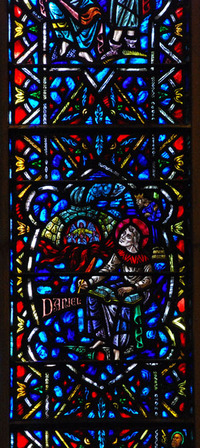

Hosea. First Presbyterian Church, Royal Oak, MI 1952, designed by Marguerite Gaudin (1909-1991) and fabricated by the Willet Stained Glass Studios of Philadelphia, PA (1954-1980).

In the left upper panel of the stained glass depiction of Hosea, (740b.c), the prophet Amos (780 B.C.), stands as a simple herdsman called by God as mentor to future prophets. Faithlessness and idolatry are rampant in the northern kingdom of Israel due to great prosperity that is limited to the wealthy. Using the marriage covenant as a metaphor for fidelity with God, Hosea is portrayed purchasing an adulterous woman that he is commanded to love and forgive in the same manner as God redeems Israel (Hosea 3:1-3).The image is a hopeful portrayal that God would restore his relationship with his people over time (John 8:1-11).

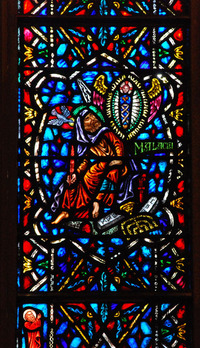

Malachi. First Presbyterian Church, Royal Oak, MI 1952, designed by Marguerite Gaudin (1909-1991) and fabricated by the Willet Stained Glass Studios of Philadelphia, PA (1954-1980).

Particular to Malachi’s representation (520B.C.), is the loss of the priestly class and the laxity in worship represented by the prophet slipping out of the temple structure, the tilted golden candlestick, and the broken stone tablets.(Malachi 4:1-3). Shoddy behavior and untenable offerings suggest that the Levitical priesthood is waning and the only chance for God’s people is portrayed in the New Covenant represented by Malachi’s intense gaze fixed on the arrival of Christ as the “son” of righteousness, illustrated as an infant from the narratives of Luke (Luke 1:46-55), and the symbolic descent of the “dove,” the Pentecostal Holy Spirit who enters Malachi’s new consciousness (Acts 10:44-48).

First Presbyterian Church of Royal Oak was registered in the Michigan Stained Glass Census by Barbara Nelson and Ruth Goode of Royal Oak, MI.

Bibliography: Show Bibliography

Bibliography: Show Bibliography

(MSGC 1996.0051)

Text by Linda Johnson, MSU American Studies doctoral candidate; photographs by Oliver Thompson, Michigan Stained Glass Census, August , 2010.