MSGC : Featured Windows : Current Window

Featured Windows, September 2005

Kalamazoo Valley Museum

Building: Horace Peck Home--razed, former home of the Kalamazoo Valley Museum

City: Kalamazoo

State: Michigan

Between 1870 and 1880, Horace Peck built a magnificent home for his family in Kalamazoo, MI. Having been president of several lumber companies in northern Michigan and Wisconsin and affiliated with some area banks, Mr. Peck wanted his home to reflect his standing in the community. The home he built was next to the old Kalamazoo Library and in effect, became a "repository" of sorts, as Mr. Peck collected Indian artifacts, fossils, seashells and other items that caught his eye. Peck died in 1903 and the family must have moved out of the house, because in 1927 it was purchased by the local school board and became the first public museum in Kalamazoo-Kalamazoo Public Museum.

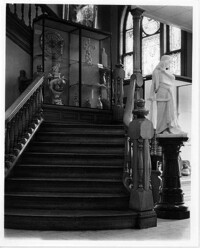

Exterior and interior views of the Peck home in 1955 when it held the Kalamazoo Public Museum. Photos courtesy of Kalamazoo Valley Museum.

One of the very interesting features in the Peck home was a very large, multi-segmented round-topped stained glass window that overlooked the entrance hall and stair landing. In 1996 a new building was constructed for the Museum (the Peck home was demolished in 1958) and the stained glass window was installed in the new Museum, now operated by Kalamazoo Valley Community College. The Peck window with its multiple sections is very ornate. As stained glass goes, residential or liturgical, its central image of swallows in flight is rather interesting and unusual. George Ferguson in Signs and Symbols in Christian Art states that in Renaissance times, the swallow was a symbol of the incarnation of Christ, appearing in paintings of the Annunciation and the Nativity. To the eye of some, the bird shown in many Annunciation paintings seems more like a dove or a sparrow, minus the long tail feathers associated with a swallow.

Elements of design in the window also reflect a tradition of Orientalist influences that emerged in Western art and decorative arts in the nineteenth century. Over 160 years ago, it was the visit to Japan in 1853/54 by Commodore Matthew Perry that ultimately affected artistic and aesthetic freedom in the West. Perry was sent by President Millard Fillmore to "open" Japan for naval vessels that needed coal, and to offset the British who been in Hong Kong and Singapore via the East India Company since 1800 or so. Perry returned with gifts from the Japanese government-porcelains, lacquers, fabrics and fans, which received little attention back in Washington, DC.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 in London's Crystal Palace had exposed European visitors to the many mechanical inventions, which were the foundation of the industrialized world at the time. This exhibition galvanized the secret world of British artists, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who since 1848 had been under the influence of writings by John Ruskin (1819-1900), an excellent watercolorist, intellectual philosopher and art critic. This group included William Morris, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ford Maddox Brown, Edward Burne Jones and William Holman Hunt. These and other artists were rebelling against the mechanized world, wanting to see a return to objects made by hand, not mass produced. They championed "art for art's sake" which they felt would return a moral and spiritual revival to society. The artists wanted to integrate art into everyday life, and were very inspired by the newness of the Japanese aesthetics, which used "nature" and things natural as the source of decoration.

Very shortly the United States was involved in the Civil War and so interest in objects of "Japonisme" was basically confined to Europe. However, by the time the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876 was held, Americans were eager for their first opportunity to see a very large collection of Japanese objects. The French Pavilion exhibited special ceramics by Limoges, which showed a decided influence from the Japanese. In the years immediately after the Philadelphia exposition, interest in Japanese decoration continued to spread. Many American and European artists visited Japan to see for themselves. Countless items were produced in Japan specifically for foreign trade. Enthusiasm towards Japanese-inspired decoration was enhanced by well-known artists who were incorporating the "style" of Japan into their paintings, such as James Whistler and the Pre-Raphaelites. These influences were seen in wallpapers, carpets, textiles as well as in furniture and stained glass. Interestingly John LaFarge, painter and stained glass artist, had been collecting Japanese art as early as the mid 1850s when he studied in France. That he married the granddaughter of Commodore Perry in 1860 undoubtedly enhanced his interest in Japanese aesthetics, as demonstrated in stained glass works he designed.

This era between 1870 and 1890 was called the "Aesthetic Movement," and it transformed daily life through decorative arts, furniture, art education in schools, museum collecting, the printed page and travel abroad. As noted in H. Weber Wilson's Great Glass in American Architecture, this was a time of great exuberance in decoration, and residential stained glass windows were increasingly found in homes. As seen in the Kalamazoo-Peck situation, residential stained glass was becoming very complex-use of jewels, stylized plant motifs, exotic flowers, fleur-de-lis, Celtic crosses, fish and painted quarries-many of these motifs could be found in pattern or ornament books such as that published in 1877 by stained glass designer Charles Booth. Many different birds were also used as decorative elements-peacocks, cranes and doves, and the occasional swallow. A photo on page 181 of In Pursuit of Beauty shows a swallow within a complex design from one of Booth's various pattern books. Other photos in this book illustrate swallows were used as a motif on diverse materials, such as an intricately carved wood bedstead from Cincinnati; a blown and enameled vase circa 1880-1890 at the Chrysler Museum in Norwalk, VA, and a brass door handle and escutcheon plate circa 1885 from Nashua, NH.

Recently, Rolf Achilles from the Smith Museum of Stained Glass in Chicago reported swallows as a focal point in a Harvey Ellis (1852-1904) stained glass design, in an Ellis designed home north of Chicago. Neal Vogel, a stained glass archivist and consultant from Chicago, described swallows used in the stained glass windows of Second Presbyterian Church, Bloomington, IL. The windows were removed when the church was demolished and currently are in storage. Closer to home, artist Tom Newton, who worked for Detroit Stained Glass Works shortly before the studio closed in 1970, provided a photo of a panel with a swallow, possibly used as a sample to display the studio's work.

Left: Second Presbyterian Church window. Photo courtesy of Ryan Dehart, BLDD Architects, Inc., Bloomington, IL.

Right: Detail of a panel by the Detroit Stained Glass Works. Photo courtesy of Tom Newton.

All other photos courtesy of Kalamazoo Valley Museum.

Bibliography:

Show BibliographyAdams, Henry, et al. John La Farge (New York: Abbeville Press, 1987).

Burke, Doreen, et. al. In Pursuit of Beauty: American and the Aesthetic Movement. (New York: Rizzoli, 1986).

Coleman, Brian D. "Design Motifs," Old House Interiors, August/September 2005.

Ferguson, George. Signs and Symbols in Christian Art. (New York: Oxford University Press), 1954.

Fisher, David and Frank Little. Kalamazoo County, MI: History and Biography. (Chicago: A.W. Bowen & Co., 1906).

Frelinghuysen, Alice Cooney. Louis Comfort Tiffany at the Metropolitan Museum. (New York: Harry Abrams Inc., 1998).

Jones, Owen. The Grammar of Ornament. (East Sussex, UK: Ivy Press Limited, 2001).

Kalamazoo (MI) Public Library Local History Collection. Historic Sites, Scrapbook #6.

Kalamazoo Valley Museum. "Kalamazoo Valley Museum: Highlights > Peck Collection" (2005). http://kvm.kvcc.edu/.

Kaplan, Wendy. The Arts and Crafts Movement in Europe and America: Design for the Modern World. (New York: Thames & Hudson in association with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2004).

Meech, Julia and Gabriel P. Weisberg. Japonisme Comes to America: The Japanese Impact on the Graphic Arts, 1876-1925. (New York: H.N. Abrams in association with the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, 1990).

Wilson, H. Weber. Great Glass in American Architecture. (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1986). (MSGC 1993.0089)

Text by Barbara Krueger, Michigan Stained Glass Census, September , 2005.