Featured Windows, October 2005

Soldiers of God: Spiritual Struggle Embodied in the Story of the Warrior Saints

Buildings:

Sweetest Heart of Mary Church - Detroit, Michigan

St. Andrew Cathedral (and St. Ambrose Chapel) - Grand Rapids, Michigan

St. James Episcopal Church - Birmingham, Michigan

St. Paul's Episcopal Church - St. Clair, Michigan

Presentation - Our Lady of Victory Church - Detroit, Michigan

Our Lady on the River (formerly Holy Cross) - Marine City, Michigan

St. Joseph Church - Adrian, Michigan

St. George Orthodox Church - Flint, Michigan

Alumni Memorial Chapel - East Lansing, Michigan

St. Mary's Catholic Church - Belding, Michigan

St. Ignatius Loyola Church - Houghton, Michigan

Trinity Episcopal Church - Alpena, Michigan

St. Paul the Apostle Church (formerly St. Joseph Church) - Calumet, Michigan

Christ Church Grosse Pointe - Grosse Pointe Farms, Michigan

Central United Methodist Church - Muskegon, Michigan

St. Michael Church - Flint, Michigan

Metropolitan United Methodist Church - Detroit, Michigan

Holy Trinity Church (razed 1987) - Ironwood, Michigan

In church after church, the population of the venerated can be crowded, particularly in places of worship where multiple icons and tributes have been displayed for any number of evangelists, apostles, saints and historical figures. Many look interchangeable in their garb of ages past, indistinguishable but for the inscription of a name here, or a symbol there that reminds the devout why someone saw it fitting to pay tribute to them in the first place. But occasionally one's eye falls on a figure that stands out from the others. Not holding a book or a tool, this saint moves, feels, struggles, bears some resemblance to the often violent and bloody tales of sacrifice and martyrdom that hide behind the otherwise placid images of other saints. Saints like this fight what we fear and succeed, and for that we find them fascinating. Two such figures are the archetypal soldier saints, St. Michael and St. George.

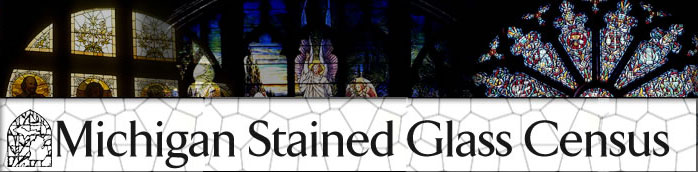

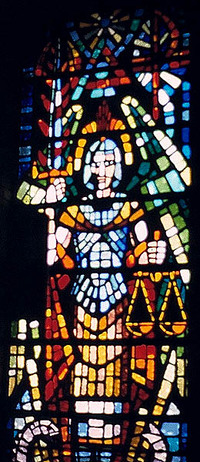

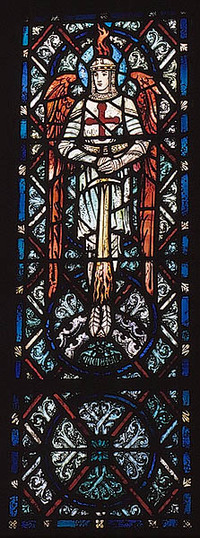

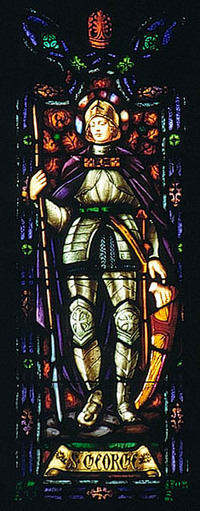

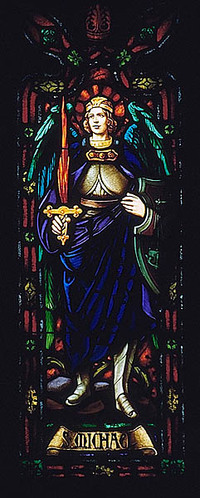

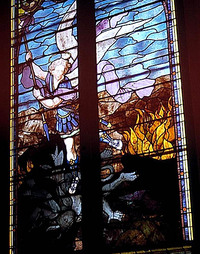

Left: The Enemy is Reason? Here St. Michael battles a quasi-anthropomorphized devil who wields a boulder bearing a motto from Enlightenment thinker Voltaire: "Écrasez l'Infâme" ("Crush the infamous thing"). The expression is typically taken to be directed at the Catholic Church or more generally at the tyranny and aristocracy of the Ancien Régime. Maker unknown, late 19th century. St. Joseph Church, Adrian, MI. MSGC 1997.0057. Photo by John Wooden. Right: The archangel Michael stands triumphant over the dragon (detail). Maker unknown, late 19th century. St. Mary's Catholic Church, Belding, MI. MSGC 2000.0018. Photo by Virginia Albert. The Archangel St. Michael, one of only three angels to be mentioned by name in the Bible (the others being Gabriel and Raphael), has a long history in Christian art, often represented with his sword as his symbol as God's warrior, and/or with a scales which represent his weighing of the souls of the departed. Other images abound of Michael in various states of battle and triumph over the devil-who is rarely represented in humanoid form but appears in any number of demon forms. The dragon incarnation of Satan that we see has its origins in the book of Revelation. Here the Archangel warrior engages in battle with Satan, appearing in the form of a dragon, casting him into hell: "And I saw an angel come down from heaven, having the key of the bottomless pit and a great chain in his hand. And he laid hold on the dragon, that old serpent, which is the Devil, and Satan, and bound him a thousand years, and cast him into the bottomless pit, and shut him up, and set a seal upon him, that he should deceive the nations no more, till the thousand years should be fulfilled: and after that he must be loosed a little season…. And when the thousand years are expired, Satan shall be loosed out of his prison, and shall go out to deceive the nations which are in the four quarters of the earth, Gog and Magog, to gather them together to battle: the number of whom is as the sand of the sea. And they went up on the breadth of the earth, and compassed the camp of the saints about, and the beloved city: and fire came down from God out of heaven, and devoured them. And the devil that deceived them was cast into the lake of fire and brimstone, where the beast and the false prophet are, and shall be tormented day and night for ever and ever." [Rev. 20.1-3, 7-10] Left: Michael pitches the devil into the fiery pit. This depiction appears to draw inspiration from Raphael's 1518 painting St. Michael and the Devil. Detroit Stained Glass Works, ca. 1893. Sweetest Heart of Mary Church, Detroit. MSGC 1992.0018. Photo by Barbara Krueger. Right: Michael and the dragon accompanied by a window depicting St. Margaret of Antioch, also with a dragon. Margaret's legend describes how the saint was swallowed by a dragon, only to be spit out when the cross she was wearing irritated its stomach. Gavin Art Glass Works, Milwaukee, early 20th century. St. Ignatius Loyola Church, Houghton, MI. MSGC 2002.0010. Photo by Richard Dunnebacke. St. Michael windows for obvious reasons are best sought in Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Anglican/Episcopal churches, where saints of the gospel as well as canonized saints are commonly chosen as patron saints and honored through ornament in the church environment. As God's supreme archetypal warrior, Michael also appears in stained glass in the context of war memorials, to honor parish members who served honorably and gave their lives in battle. A post-World War II memorial window depicting Michael, sans dragon. Maker unknown, 1947. Note the coat of arms with a red cross, commonly associated with England's St. George. St. Paul's Episcopal Church, St. Clair, MI. MSGC 1996.0056. Photo by Beryl Levy. Another soldier saint who is occasionally associated with Michael and whose legend has captured the imagination of artists and their patrons seeking to convey the triumph of the Christian soul over a tangible evil is St. George. Now the ubiquitous patron saint of England and a popular patron saint of Orthodox and Episcopal churches, George as a genuine historical figure is elusive and difficult to separate from a hagiography that has evolved and branched across Europe since the 4th century. This person was likely a martyr of the 3rd or 4th centuries, probably killed in Palestine. There is some uncertainty as to whether this individual actually was a member of the military and what the details of his death were, but the legend tells that George was a soldier of some high rank who lost his life, following a shift in Roman culture whereby the emperor Diocletian in AD 303 forbade the practice of Christianity. This resulted in the persecution and execution of Christian soldiers and other high ranking public figures who had previously been able to worship openly. There is record of several soldier saints during this period with the name of George whose deaths may have contributed to the larger legend and cult of "George of Cappadocia." George, the soldier saint. Conrad Pickel Studio, New Berlin, WI, ca. 1971. St. George Orthodox Church, Flint, MI. MSGC 1997.0138. Photo by Charles Lowell. Soldier saints like George developed large cult followings during this period, which would explain their continued representation in Eastern Orthodox churches to this day. Soldier saints were often said to be assistants of St. Michael who were persecuted at the hands of pagan emperors, and by the 6th century it was common in legend for George to be paired with St. Michael. George was introduced to the rest of Europe by way of the Crusades and many countries claimed George and his legend as their own, contributing to the proliferation of the saint's cult. Post-war Episcopal interpretations of a knightly St. George, each bearing his characteristic sign of the red cross. Left: J. Whippel & Co. Ltd., Great Britain, 1960s. Trinity Episcopal Church, Alpena, MI. MSGC 2005.0012. Photo by Cathy Green. Right: Lamb Studios, Tenafly, N.J., date unknown. St. James Episcopal Church, Birmingham, MI (built 1959). MSGC 1996.0003. Photo by Barbara A. Stokel. Evidence of George's foundations in Britain likely go back to the 6th century. By the 11th century a number of English churches were dedicated to the saint and by the later medieval period written English accounts of the legend began to suggest that George had visited and even been born in England. In Britain, George's symbol of the red cross on a white flag has been incorporated into the national flag, the George Cross is one of the highest awards for bravery and his name graces numerous streets, squares and churches around the country. Since the middle ages, his image has been represented in countless ways in art and literature, including almost 100 known medieval wall paintings in England alone. More recent tellings of George's legend (since the 10th century) involve his rescue of a princess from a dragon. In the story a dragon was threatening a town and to keep it away, the townspeople first sacrificed sheep, and then their children. Eventually a king's daughter is chosen as the sacrifice and George appears, offering to kill dragon. After wounding it, he asks the princess to lead the dragon back to the village where he tells the people that he will kill it if they convert to Christianity. While a tradition of saints slaying dragons has existed (not the least of which being Michael), George's story appealed to the English royalty and gentry that commissioned artwork and patronized churches. His imagery blended well with English ideals of military service, chivalry and courtly love. "The Virgin's champion," as British Cultural historian and medievalist Samantha Riches calls him, George came in England to represent the ultimate protector of purity, honor and the nation, continuing to appear in many forms in British popular culture. That imagery can be seen in American Episcopal churches and also in non-denominational or secular contexts, where the battle of the soldier and the dragon can come to embody other types of struggle. A Cold War-era George figure protects family and nation as an icon of patriotism, as the dragon contorts to the form of a Soviet hammer and sickle. Willet Studios, Philadelphia, Marguerite Gaudin designer, 1952. Michigan State University Alumni Memorial Chapel (non-denominational), East Lansing, MI MSGC 1992.0003. Photo by Bill Heater. Left: St. Michael and dragon. Mary Giovann, Designer. Fabricated by Detroit Stained Glass Works. Presentation - Our Lady of Victory Church, Detroit (built 1955). MSGC 1996.0065. Photo by Una B. McKenzie. Right: St. Michael and dragon. Ford Brothers Glass Company, Minneapolis, 1907. St. Paul the Apostle Church, Calumet, MI. MSGC 1993.0040. Photo by Eric Munch. Left: St. Michael, with his traditional symbols of sword and scales. Maker unknown. St. Michael Church, Flint, MI (built 1965). MSGC 1997.0080. Photo by Sue Meissner. Right: St. Michael, with a sword and shield. Unknown maker, 1876. Cathedral of St. Andrew , Grand Rapids, MI. MSGC 1995.0028. Photo by Thomas R. Bochniak. Left: A floating St. Michael, with flaming helmet and sword. Imagery of Michael and George are known to appear in older Methodist churches such as this, probably because of Methodism's historical ties to the Episcopal church. Charles Connick Associates, Boston, MA, date unknown. Metropolitan United Methodist Church, Detroit, MI (built ca. 1925). MSGC 1993.0034. Photo by Ernest G. Aruffo, Jr. Right: St. Michael and dragon. Clement Heaton, Long Island, NY. Christ Church, Grosse Pointe (Episcopal), Grosse Pointe Farms, MI, ca. 1935. MSGC 1993.0080. Photo by Michael DeFillipi. St. Michael. Maker unknown. Holy Trinity Church, Ironwood, MI (built 1920, demolished, 1987; windows transferred to collection of Ironwood Historical Society). MSGC 1993.0091. Photo by Ray Maurin. St. George (left) at rest and St. Michael with a flaming sword (right). Giannini & Hilgart, Chicago, ca. 1930. Central United Methodist Church, Muskegon, MI. MSGC 1995.0020. Photos by Carlean Erickson and Mary Lou Hubbell. St. Michael and three-headed dragon, St. Peter's in Rome visible in background. Artistic Glass Painting Co., Cincinnati, 1904. Holy Cross Catholic Church, Marine City, MI. MSGC 1996.0115. Photo by Agnes Griffor.Bibliography: Show Bibliography

(MSGC 1997.0057, 2000.0018, 1992.0018, 2002.0010, 1996.0056, 1997.0138, 2005.0012, 1996.0003, 1992.0003, 1996.0065, 1993.0040, 1997.0080, 1995.0028, 1993.0034, 1993.0080, 1993.0091, 1995.0020, 1996.0115.)

Text by Michele Beltran, Michigan Stained Glass Census, October , 2005.